The range: a case study in Neapolitan repertoire

An analysis of possible graphical conventions in notation, colors and effects which Neapolitan composers such as Perez, Porpora and Anfossi might have planned when they chose to score for “fagottino“

By Giovanni Battista Graziadio

The use of the bassoon in Neapolitan repertoire, the subject of my PhD research, brought my attention to two notable examples where small-sized bassoons are expressly requested by the composers. Forty-four years divide these two cases and the range, the use, and the notation of the “fagottino” appears completely different, despite referring to the same range, as will be discussed. In this article, another remarkable example will be examined first, in which the composer mentions only full-size bassoons, scored in the exceptionally high range. Through consideration of notation and compositional aspects, I will illustrate why “fagottino” would be more recommended also in this case.

This repertoire offers the opportunity of further speculation on the implementation of small-sized bassoon in performance practice. Moreover, it gives an orientation on how “fagottino” was used, how its range was exploited, and how its part was noted, at least in Neapolitan repertoire and/or by Neapolitan composers.

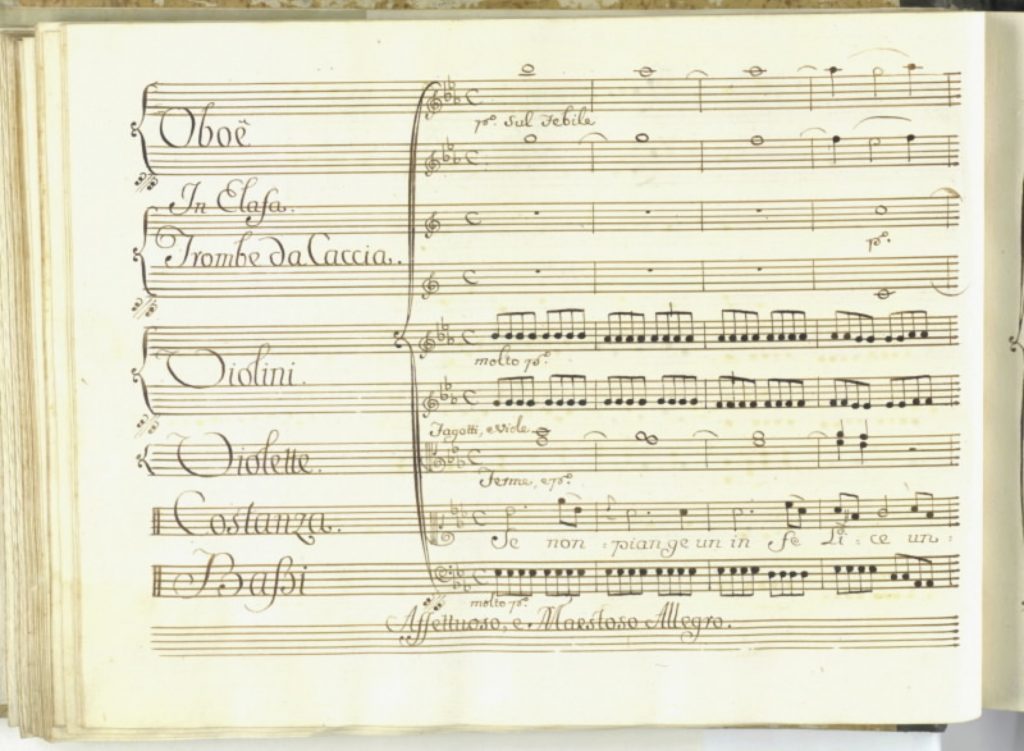

An excerpt from Scene I in the first act of L’isola disabitata by David Perez (Lisbon 1767) is a good example of very refined orchestration, with concertino passages for each instrument indicated in the score. [1] Dynamic markings and effects are specified in each part leaving nothing for granted, to be certain to reach the result intended by the composer. This kind of care with markings is seen in many compositions by Perez, including his opera Solimano.

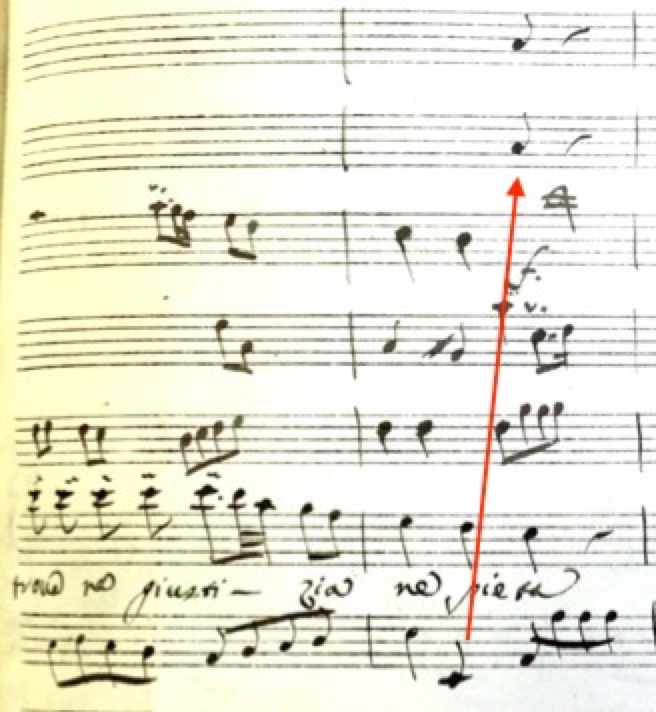

Despite this, the indication “fagotti con le viole”, which occurs several times in this scene, might be misinterpreted and literally associated with the use of full-sized bassoons (Fig. 1). A range from g–d’’, pianissimo high b’’, extraordinary high and long notes held over bars, agile passages in this extreme bassoon range, and jumping from the basso continuo line to viola parts is what is required from the bassoonist playing these parts.

Even if it cannot be ruled out that exceptional players could have easily approached this music with their skills and bassoons, the use of “fagottino”, or octave bassoon, is what would give the exact character needed for this music: lightness, agility, modulating articulation, and dynamic flexibility are required to accompany the soloist, with these typical mid-18th-century-Neapolitan-style viola parts, something not easily done with a full-size bassoon in this range. To achieve this purpose, even the viola is used in its high range to produce a bright and light sound. Moreover, it must be excluded that bassoons would double the viola parts an octave lower, because this would give a heavy and grotesque effect to the accompaniment of the violas, not to mention the inverted chords that would result. In some moments, there would even be enough time for the player to switch from a full-size bassoon to a “fagottino”, but this is not always possible.

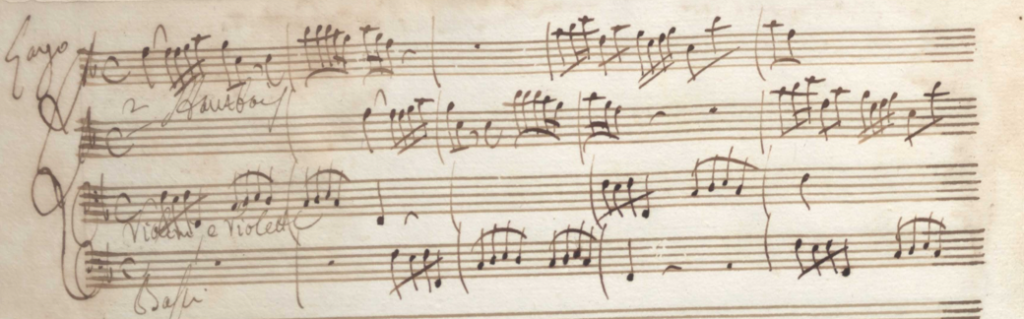

Graphical conventions in these scores can be very controversial. For example, it is possible to find thousands of examples in Neapolitan music where the viola should just play the bass line, usually indicated with ‘viola’ at the beginning of the bassline, or just “Viola col basso” or “Viola col B,” as Perez does. In works by Vivaldi, scoring instructing the violins to play a “bassetto” part is always found written in bass clef, also when the continuo group is not playing (Fig.2).

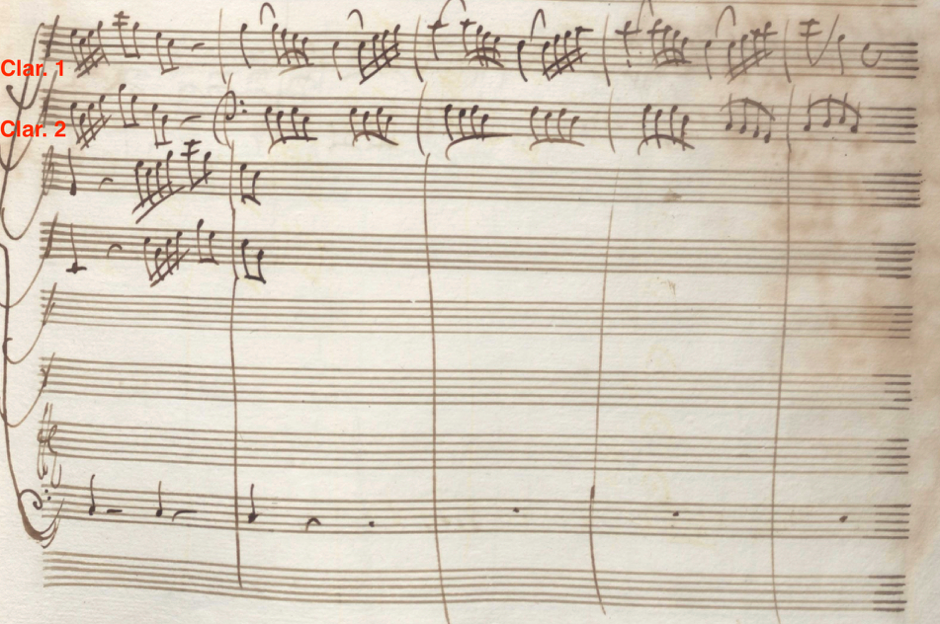

Obviously, this does not mean that violins or violas are playing in the bass clef range, but the bass clef is just underlining the function of the part and perhaps suggesting the right attitude to the player, too. In Vivaldi concert RV 560 for two oboes, two clarinets and strings, the clarinets parts are written alternating violin and bass clefs throughout the whole piece. Sometimes, when one clarinet is accompanying the other, (e.g. one part has a clear melodic function and the other has a bass part), the melodic part is written in violin clef and the other in bass clef (Fig. 3)

Usually what is written must be formally correct, even if it is just a graphical convention on paper and there is another sounding result. In these scores by Perez, the “fagotti” are in fact very close to the role and the range of the violas.

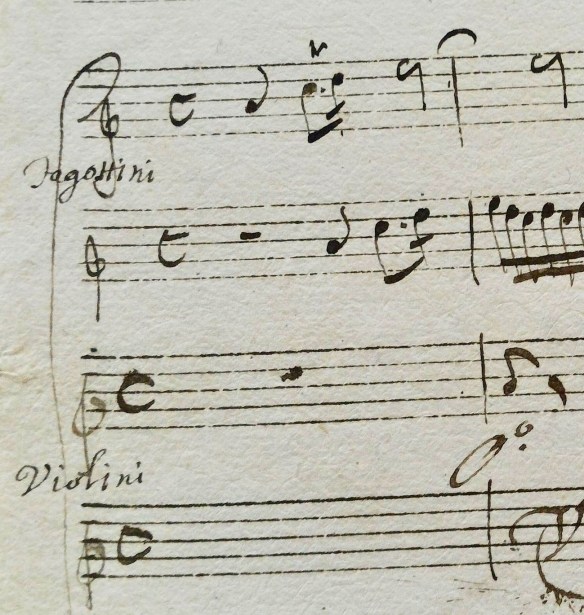

The score from Porpora’s Siface, Act III, Scena I (Rome, 1730), which clearly indicates the use of “Fagottini”, should take away any doubt about the range of these instruments. This is very useful because it gives a different perspective when looking at music scoring an exceptional high range for bassoon, like the one of Perez where just “Fagotti” are indicated. Porpora writes the “Fagottini” parts in violin clef (Fig. 4) while the viola part is “col Basso” from the beginning of the scene, apart from some bars.

Looking particularly at the second “fagottino” part, it is possible to see many sudden changes from violin to bass clef, again with the conventional indication “col Basso”. Sometimes the quick change of octave in the “fagottino” line would be more than two octaves; this is surely something unwanted, if we literally insist on what it is written (Fig.5).

The “fagottino” plays in violin clef in the real range as indicated by the composer and jumps to the bass line an octave higher as a violin or a viola would do. In fact, Porpora alternates the violin clef with the bass clef to indicate when the “fagottino” switches from its obligato part to a sort of continuo function and he is indeed using these small bassoons in their full range from a to f’’.

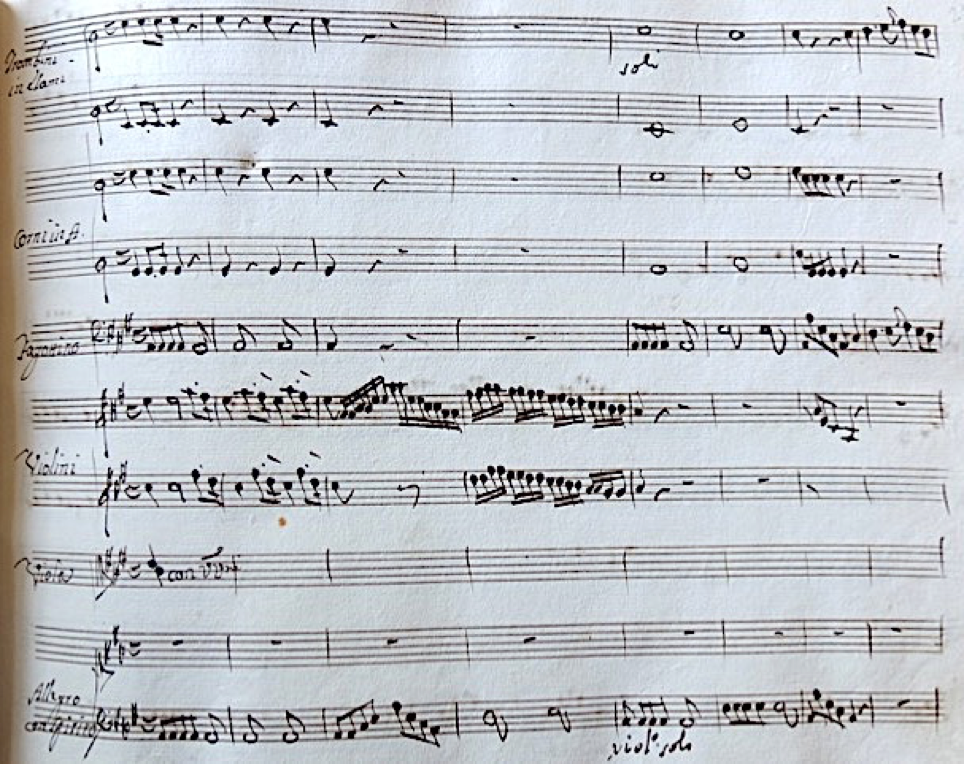

Forty-four years after Siface by Porprora, in Achille in Sciro by Anfossi (Roma 1774), Act II, Scena XIII, “fagottino” is scored along with “trombini”, “corni” and strings (Fig. 6). This is another excerpt full of musical indications, and here the viola part is almost continuously doubling the violins parts, so that viola I plays with violin I, and viola II with violin II. “Fagottino” is placed in the score just after trumpets and horns, in the upper part of the page. The “fagottino” line follows the continuo line most of the time, but there are moments where it matches the accentuation of the musical comments of trumpets and horns.

Differently from what is seen in works by Perez and Porpora, the “fagottino part” is notated in bass clef here. The range is from A to e’, keeping to what is written, like a typical full-size bassoon line. But there is not only the indication of “fagottino” to suggests a change of colour for this piece; for example, the effect of having the violins doubled by the viola is the first big change of colour; the second is a very meticulous concertino writing for the bass.

The bass line has many dynamic indications, and always plays when horns and trumpet are not playing, except for the last 41 bars and for a few other bars during the aria. Even if the violoncello always plays through the whole movement, another change of colour is indeed found when Anfossi indicates “violon. solo” (violoncello solo), to have only this instrument playing every time winds are making their musical comments.

Every time the indication of “violoncello solo” occurs, the “fagottino” is always playing/doubling the part. The “fagottino” part looks like a replacement of the function of the viola when it plays along with the basses, but at the same time, fulfilling the need of being part of the sound of the brass.

For all these reasons it is possible to assume that also in this aria, the indication “Fagottino” refers to an octave in the same range of a viola. The actual sounding range of this part would be instead from a to e’’, again going against what is literally written in the score. The reason why it is notated in bass clef could be merely pragmatic and/or linked once more to that graphical convention, which, in this case, would also suggest the function of such an instrument, i.e., a “bassetto” accompaniment with a specific colour.

In conclusion, these three cases gives the opportunity to speculate that even if the range exploited by these three composers is very similar (Perez from g–d’’, Porpora from a–f’’ and Anfossi from a–e’’) a notation with violin clef would suggest more a soloistic/obligato part, the bass clef indicates a role of continuo/”bassetto”, and the alto clef would suggest a concertino viola role with typical middle-part tasks.

Endnotes

[1] I am very grateful to Iskrena Yordanova, who pointed out what follows about the handwritten information reported on the manuscript in I-Nc 30.4.5 “Azione teatrale in un atto Rappresentata a Palermo nel 1748 (vedi Fetis)”: “This information was added later, and has caused confusion in descriptions of the work in various articles and the main databases with regards to the year of its first performance. According to the dictionaries mentioned, Perez’s Isola was given in two versions: a presumably first performance in Palermo, in 1748, and another in Queluz, in 1767. in fact François-Joseph Fétis mentions in his Biographie universelle des musiciens, an opera by Perez given in Palermo, in 1748, with the name L’Isola incantata. It is not at all possible that the work mentioned by Fétis was this L’Isola disabitata with a libretto by Pietro Metastasio. The text of this libretto was written in 1753 and its first performance took place on 31 May 1753, at the Palace of Aranjuez, with music by Giuseppe Bonno. One of the objectives of the present critical edition is to rectify this mistake and establish the first performance of L’Isola disabitata by David Perez as having taken place in 1767.” See ISKRENA YORDANOVA, L’isola Disabitata di David Perez (critical edition), Rome: Istituto Italiano per la Storia della Musica 2017.